Why management quality should matter for investors

by Pravin Palande, Samar Srivastava | Feb 2, 2015

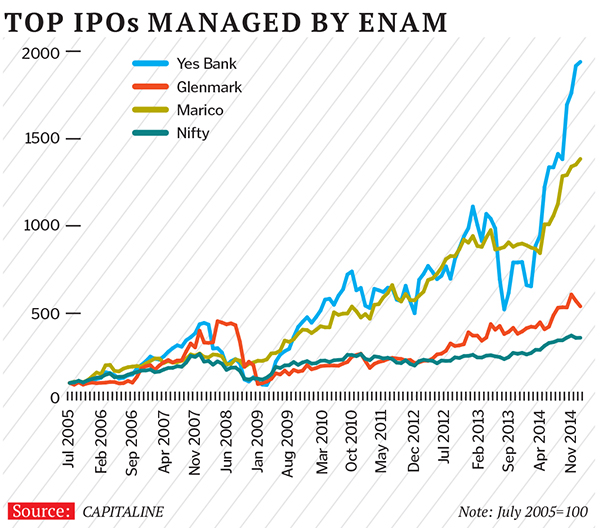

The quality of the people running the show can make or break an investment decision, says master investor Nemish Shah

Nemish Shah is a reclusive man. He has not met the media for over 15 years. Even after Axis Bank took over his firm Enam Securities in 2010, he was neither seen at press conferences nor were his pictures bandied about in the media. So when he agreed to talk to Forbes India about his investment philosophy, we were excited. We met him at his sprawling office in downtown Mumbai’s Express Towers with stunning vistas of the Arabian Sea. The office is simple with light brown furniture and plenty of open space. There is no receptionist. It is quiet but it does not have the coldness of a private equity firm.

Shah, 59, co-founder and director of Enam Holdings, comes out and smiles warmly. He ushers us into his room at the appointed time of 12.15 pm. Tall and fit, the master investor, walks in a brisk manner. And we quickly get down to business.

As someone who has seen several market cycles, we are curious to understand the evolution of Shah’s investing philosophy over the years. Investing, according to him, is simple and complicated at the same time, in a sense a lot like art. He says while investing in India follows the same rules as elsewhere, there is one crucial difference—here, the quality of the management has to be considered closely. “Abroad one can go by what is there in the books, but here you have to add one additional layer—the management,” says Shah. But as long as the management is focussed and understands allocation of capital, he is comfortable with the business. What he isn’t comfortable with are companies that are hasty and raise capital regularly. In fact, Shah has ignored many companies where the management did not give him the right vibe.

He then dons his analyst’s hat and gives an example of how a company allocates capital. After quick calculations on an imaginary balance sheet, Shah discusses its return on capital employed (ROCE) numbers. “If the ROCE numbers are less than nine percent, the company is a wealth destroyer. What is the point of being in the business if you can’t generate a sustainable ROCE,” he asks. Ignoring his buzzing iPhone, he continues talking numbers. Shah evidently takes comfort in numbers and uses them as a weapon or a shield, depending on the discussion. It is an art that he has mastered over many years.

If someone has no respect for capital allocation, it shows up, sooner or later, he says, pointing to the numerous examples of over-leveraged companies that saw their share prices fall. For instance, the infrastructure space, in which promoters took money on high traffic projections, low interest rates and quick completion of projects. In effect, they left very little room for error, says Shah. If any of the projections were to go wrong, the company would have a hard time paying off its debt.

It’s not just unsustainable debt that Shah shies away from. He feels a company might often be operating in a sector that suffers from external problems but if the management is good, it can find a way to survive and grow in that market. Take commodities companies like JSPL (Jindal Steel and Power Limited) which had a market cap of Rs 13,545 crore and was priced at Rs 156 per share on January 14. The stock was available for Rs 2 in 2001. It has delivered a return of 37 percent annually against 15 percent for the index over the last 15 years. He gives credit to the company management for such a stellar return.

Since promoters and management are the key to his analysis, he prefers to meet them to get an idea of how they look at business. Shah has always stayed away from firms where promoters are constantly raising capital and diluting equity, and who constantly track their stock prices. What’s most important to him is the way they plan to fund future growth. He is wary of excess leverage, but does not have a negative view of a company that needs to spend more in the short term to enhance its competitive edge.

Much has changed since Shah first entered the market in the 1980s. “Firstly, the breadth of information available on a company and on a business,” he says. Shah remembers when he would write orders at the trading ring and run to the relevant broker to get them executed. In those days, there was huge information asymmetry in the market and smart investors were able to exploit it.

Sample this: Till the 1990s, companies would report their earnings only once a year. For the rest of the time, investors were just fishing in the dark and depending on informal information channels to gauge how businesses were doing. For the auto industry, they would check with dealers. Investors in pharma stocks would check with chemists. Companies were not interested in meeting them, so analysts were focussed on horizontal research where it was important to be on ground and question dealers and customers.

It was only in 1993 that Infosys ushered in a new era of transparency by declaring results every six months and, later, every quarter. Things changed dramatically as regulators ensured that companies declare their market activities to the stock exchanges on a regular basis. Investors now have all the data and analyses at their disposal to the extent that it has even introduced noise into the system. “Analysis is leading to paralysis,” he says.

Shah is proud to point out that it was Enam that took Infosys public in 1993. He had been impressed by NR Narayana Murthy’s vision, but he did not believe that Infosys would actually go on to become the bellwether of the stock market. In fact, the issue was undersubscribed and his team and he had to convince a lot of people to invest in the company. “But after Infosys, there were many companies in the IT space that went public. But only a few made their mark,” he says, emphasising that the reason for Infosys’s success was the quality of its management.

In the following years, the IT industry went through a dotcom boom and only a few companies survived the bust. He sees a similar kind of valuation madness in the ecommerce business today. “It was only a few years ago that some of the biggest conglomerates in India made a foray into the retail business and now they see competition from young companies like Flipkart,” he says.

His take on the frothiness in the valuations of ecommerce companies is somewhat contrarian. Unlike conventional businesses, where the growth patterns are linear, ecommerce does not have a straight-line growth path. In that context, it is very difficult to challenge these companies on their potential numbers over the next few years. “And when these cannot be discounted to a present value, you have investors paying any valuation for them,” he says. However, Shah doesn’t think valuations in the sector have reached a bubble as the potential size is so vast that “we may not even have wrapped ourselves around the true potential of the business”.

Given Shah’s approach to measuring a business, one would have to agree. First, he looks at the size of the opportunity, which is clearly there for ecommerce companies. Second, the quality of the management—most ecommerce players have shown that their managements are forward-looking. Last is the entry price. Here, while valuations may be stretched, there is the possibility of non-linear growth, which will always command a premium.

Shah is also bullish about the present government and its performance, “I have not seen such an environment in my entire working life since I took up my first job. These are truly good times for India. I think that there is some scepticism among many people, but they will be proven wrong,” he says.

Shah, even as he points out the several pluses of the new government, veers to the topical subject of oil prices. For one, he is pleased that the government is not showing a populist tendency, giving away the benefits of lower oil prices to the consumer. And then, he does a quick mental calculation and tells us that “this year we will be current account surplus and there will be no burden of fiscal deficit”. He also says that the rupee is now one of the most stable currencies, maybe after the US dollar and the Chinese renminbi. But the big concern for him is how the government will get into the capex cycle. “Will the government start spending first?” he asks, wondering how both the government and the industry can create demand and growth by taking advantage of the present situation. “It is so difficult to get land. And it takes more than five years to get a cement plant going. So starting the cycle is not easy,” he says. However, there will be enough opportunities to invest.

“But then it is always luck that decides success,” he says, looking at the pictures of spiritual gurus adorning his walls. “Who am I?” is the question he is trying to understand. And it is a very difficult question to answer, Shah says. Perhaps that is why he is reclusive and spends his time introspecting. His spirituality is evident. Consider that Shah has avoided investing in tobacco, hotels and liquor as they don’t fit in his internal philosophy. He wants to live a quiet life, coming to office at 8.15 am and going home by 3 pm, he tells us.

As the meeting ends, he walks us to the elevator, saying he is always ready for a chat, but is not willing to engage in just yet another media interaction. He had, at the outset, said a firm ‘no’ to photographs and voice recordings.

As we say goodbye, we ask if there are any investment gurus who he follows or reads. “The letters of Warren Buffett,” he says. The elevator has reached us at that point and Shah shakes our hand again, for the fourth time since we left his corner office. And we exit, with much to mull over, and thinking that introspection can be an infectious thing.